In this series, we will explore how to write a compiler for a small subset of C to LLVM in Haskell. Our language, Micro C, is basically a small subset of real C. We'll have basic numeric types, a real bool type, pointers, and structs. At the end of the series, we'll have a beautiful executable, mcc (Micro C Compiler), that takes one .mc source file and produces an executable.

Why another LLVM tutorial?

Stephen Diehl's translation of the kaleidescope tutorial provides an excellent introduction to building a simple language using Haskell and LLVM. However, it uses an older version of LLVM than is currently available. In particular, it was written before the IRBuilder module was added to the Haskell bindings and required users to write a lot of plumbing themselves which is now handled by the library. Also, although kaleidescope is a fine teaching language for compiler construction, our version of C, stripped down though it is, is still meatier, and will allow us to dive a little deeper into LLVM features. Moreover, basically everyone already knows C1, and being able to compare our compiler's output to clang's is an excellent debugging resource.

Who is this tutorial for?

This tutorial assumes some familiarity with Haskell. To learn the language, consult the resources mentioned in this superb Stackoverflow answer. For reference, the Haskell used in this project falls somewhere in what that answer would deem the early intermediate category, as there are a lot of Monad transformers, but no fancy GADTs, TypeFamilies, recursion schemes, or any of the other billion extensions that GHC has to offer. While all of these advanced language features could actually be quite helpful in writing a compiler, I've left them out of mcc in order to attempt to be more beginner friendly.

Getting set up

Development environment

The full Haskell source of the compiler lives at https://github.com/jmorag/mcc.git. Getting the LLVM toolchain set up is rather involved, so in lieu of providing you with build instructions, my recommendation is to just use nix. At the root of the repo, there is a shell.nix file that you can use to drop into a shell with the necessary Haskell libraries, cabal, and clang. If running nix-shell --pure --run 'cabal new-clean; cabal new-test' runs smoothly, then everything should be set up correctly. If not, please open an issue.

Haskell tooling is constantly in flux. When I started writing Micro C, I used vim and ale, but switched to emacs and intero halfway through, both with stack. As of April 2020, I've replaced intero with dante and switched back to plain cabal, as it plays better with nix. I've been meaning to look into ghcide but dante works well enough for me and I haven't found the time or motivation to switch. In the case that these tools don't work or take too long to setup, ghcid is a great fallback.

Dependencies and project-wide language extensions

Following this excellent blog post by Alexis King, we'll specify our project information in a package.yaml2. The first few lines just specify project name and author

name: mcc

version: 0.1.0.0

github: jmorag/mcc

synopsis: A microc compiler in Haskell

author: "Joseph Morag"

license-file: LICENSE

category: Compilers/InterpretersWe will also increase GHC's warning levels to catch more potential problems. Some of these can be annoying, but they solve many more headaches than they cause.

ghc-options: -Wall

-fno-warn-name-shadowing

-Wcompat

-Wincomplete-uni-patternsNext, we specify our dependencies.

dependencies:

- base >= 4.7 && < 5

- mtl

- array

- containers

- text

- string-conversions

- directory

- process

- unix

- filepath

- bytestring

- prettyprinter

- pretty-simple

- llvm-hs-pure >= 9 && < 10

- llvm-hs-pretty >= 0.9 && < 1

- megaparsec

- parser-combinators

library:

source-dirs: src

executable:

main: Main.hs

source-dirs: app

dependencies:

- optparse-applicative

- mcc

tests:

testall:

main: Testall.hs

source-dirs: tests

dependencies:

- tasty

- tasty-golden

- tasty-hunit

- mccFinally, we'll enable some language extensions. I've only enabled two globally for this project.

default-extensions: OverloadedStrings, LambdaCaseOverloadedStrings is a necessary evil to deal with Haskell's infamous string problem and LambdaCase is a tiny syntactic extension that lets us get away with making up fewer variable names, thereby solving a hard problem in Computer Science.

Project overview

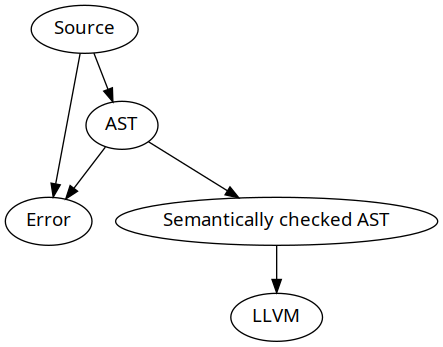

A compiler's job is to take one or more source files, parse them into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), check them for semantic errors, and if they have none, lower them to an Intermediate Representation (IR), optimize said IR, and produce an executable for the target CPU.

Different languages treat these steps differently. Lisp's syntax resembles an AST so closely that parsing is almost a no-op, whereas C has infix operators and block statements that make the transformation from a sequence of bytes to an AST nontrivial. Many dynamic languages perform almost no semantic analysis whatsoever before runtime, whereas on the other side of the spectrum, dependently typed languages perform such intricate analyses that they can prove that their programs will terminate. Our C dialect falls somewhere in the middle; we will reject programs at compile time that assign a float to an int type variable, but we will make no effort to do any type inference or termination checking. We will also not concern ourselves with target specific code generation, leaving that to LLVM. The basic architecture will be something like:

Now that we've laid out the preliminaries, we can actually start coding in part 1!

and if you don't but want to work with LLVM, you should really really learn it, as LLVM is designed first and foremost as an intermediate representation for C and C++

The native cabal format recently got support for common stanzas, eliminating much of the need to use hpack. Also, FPComplete now recommends committing the generated cabal files, so in the future it might be a good idea to write an mcc.cabal by hand instead.